(download as a pdf - 2.9Mb)

Skin tears are small avulsion injuries. They occur most commonly in older adults and are the result of friction and shear. The pretibial area is most commonly involved, but the lesions also occur on other anatomical areas with thin or fragile skin, such as the dorsum of the hand or the elbows. Skin tears may be caused by an accident, but in the frail skin of older adults they may even be caused by the removal of an adhesive dressing. The exact incidence of skin tears is not known, but data gathered in a long-term care institution indicate that more than 95% of all injuries not related to falls were actually skin tears and bruises(2).

Skin tears may involve not only the epidermis but can also be full thickness. Usually, the lesion retracts somewhat and part of the underlying tissues is visible. The diagnosis is straightforward(2).

Although a small percentage of patients will develop wound healing problems, most lesions will heal fairly quickly with proper wound care, including moisture retentive dressings(2).

As we get older we undergo changes that make our skin more susceptible to damage such as skin tears and bruising. A number of specific skin changes have been related back to changes in hormone levels as we age, such as the effects of estrogen on inflammation and dryness(3, 4). The accumulation of radical oxygen species (ROS) in the mitochondria of cells has also been shown to induce senescence and increase terminal differentiation; this has been implicated in the thinning of ageing skin(5, 6). But as well as the intrinsic factors of aging the skin also has to face extrinsic influences. The two most significant of these are sun exposure and smoking, which have a significant effect on the skin’s elastin and collagen(7, 8). A complex diagram of some of the biochemical changes can be seen in Appendix A. Nutrition and hydration also play a role in the resilience of the skin. Some of the physiological changes include:

Not only do these changes have an obvious cosmetic and self-esteem impact but they can also impact on quality of life with skin conditions such as xerosis prutitis, and eczema being widespread in the older population(9). And not only that but the simultaneous changes in immune function as well as skin structure and function produces higher levels of autoimmune skin disorders. The exposure to new pharmaceuticals increases the risk of autoimmune drug reactions that manifest in the skin. These may include pemphigoid or pemphigus disorders and small vessel vasculitis. Then there’s the possible re-activation of dormant viruses such as Shingles(9). With all this, do we really need a skin tear?

But it’s not just the changes in the skin that make us more likely to get a skin tear. Other changes that may be experienced include (certainly not comprehensive):

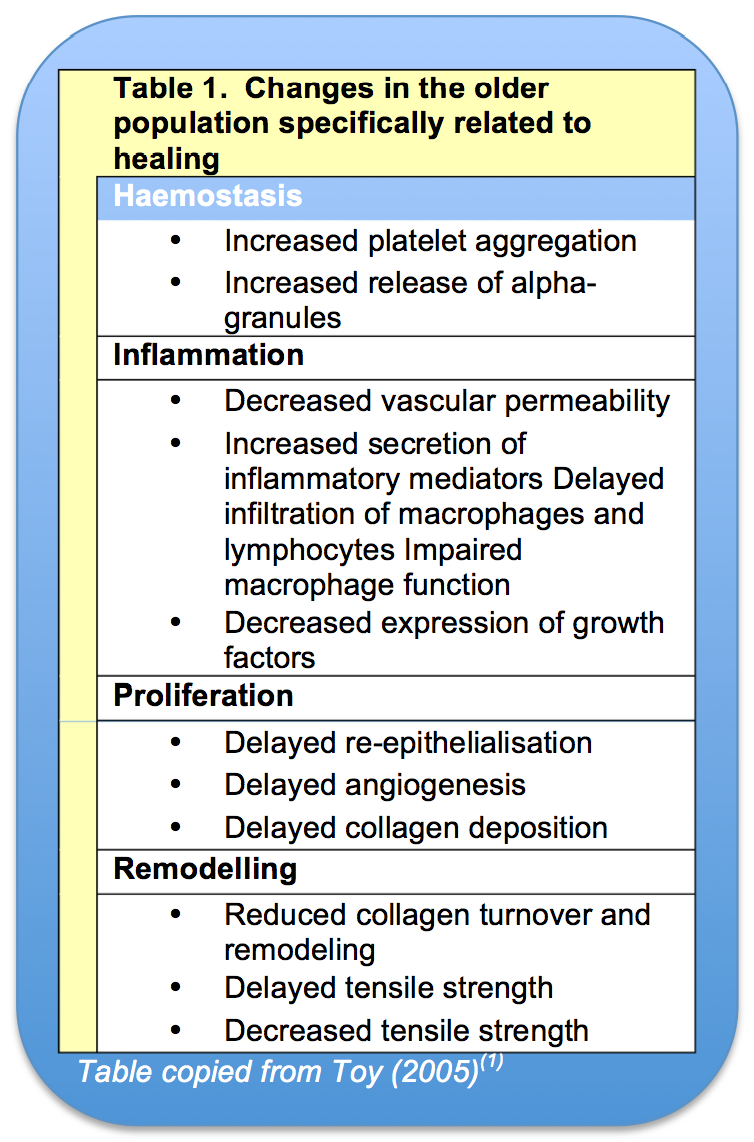

So let’s say we have a skin tear, and now we have to heal it. It is argued that the effects of ageing do not directly, negatively impact on wound healing but that it is all the confounding factors that go along with ageing(13) such as polypharmacy, comorbidities, and alterations in nutrition and hydration. The reasoning behind this thought is that the body has so many redundant systems for healing, that no matter what becomes less efficient during the healthy ageing process there are enough systems remaining to make up the difference … if just a little bit slower(14). Table 1 lists how the various stages of healing may be affected by ageing. So when we do our assessment of systemic features that may impair healing, while we may list healing as ‘slowing healing’ it will be other assessment items like venous insufficiency or low serum albumin that will need to be targeted in the management plan.

So what’s the plan?

Management of the skin tear is straightforward and follows the basic wound bed preparation principles. There is a simple flow chart that can be incorporated into a skin tear package in Appendix C if you feel this would be beneficial in your area.

The use of anticoagulants and antiplatelet medications may inhibit the normal clotting progress and slow healing by delaying the healing process(15). Management of the bleeding patient involves both the immediate management of the bleed and the post bleed assessment. If there is very little bleeding, clean first (see below), then manage the bleed.

If you do not expect the patient to have any coagulation problems the basic bleeding management involves pressure and elevation(16). Lay the patient down, elevate the bleeding area, cover with an absorbent pad and apply pressure. Allow the patient to sit like this for 5 to 10 minutes. Watch for strikethrough and adjust as needed.

For the patient who may have a reduced ability to clot, calcium alginates have been reported as having haemostatic properties. Do the same as above but with a calcium alginate dressing (such as Kaltostat) underneath the absorbent pad. For more severe bleeding you can use adrenaline soaked gauze if you have a medical officer present (beware of rebound bleeding and ischaemic necrosis)(17).

Special training is recommended for nurses in palliative care wards that look after cancer patients. Patients with fungating tumours are at a high risk of a catastrophic bleed from these tumour sites(17), which may be disturbed by the skin tear or whatever caused the skin tear.

Assessment of your patient needs to include circulation obs below the site of the bleed, standard obs to watch for hypovolaemic shock, and should include a review of pathology results and medications to ensure clotting profiles are within acceptable limits.

While you’re waiting for the bleeding to stop, start running through your assessment. Consider items in the patient’s history as well as regional and local observations that would impair healing and devise a plan to manage these risks. I find using a combination of assessment tools such as HEIDI(18) and TIME(19) help to collect the most relevant information. An example of a tool that combines these to develop a wound management plan can be seen in Appendix D. For documentation purposes it is good to be able to describe the extent of the skin tear. Silver Chain Nursing Association and Curtin University designed a skin tear classification chart that is very helpful in recording skin tear type. The system can be seen in Appendix E. You will also need to address the findings of your pain assessment at this point.

Cleaning should be done in accordance with your local wound cleaning policy. You may use normal saline, potable water, or a specialized cleaning solution such as Prontosan; different solutions have their merits(20). Routine cleaning with topical antimicrobial solutions, while reducing bacterial load may actually inhibit wound healing, possibly even contributing to a wound getting stuck in the inflammatory phase(21). More evidence is needed to determine a specific set of solutions, pressures and techniques to determine optimal cleaning regimes(22).

The aim of cleaning is the same, regardless of your technique. We want to ensure the wound bed is free of any contaminants that may hinder the healing process. This can be foreign matter, clots or obviously non-viable skin. You may need to incorporate soaking or the use of cotton-tipped applicators, forceps and iris scissors during the cleaning process. Don’t just clean around the skin tear, fold the flap back and clean out anything that has become trapped under it.

Once the wound and flap is cleaned gently roll it out to its original position as best you can. However, too much tension has to be avoided because this may result in flap necrosis(2). Steristrips are often used to pull shut, and hold shut a skin tear. It is true, they do hold the flap in place, but the downside is that this may create too much tension and result in flap hypoxia. Also, the steristrip itself is a foreign body. Does it need to be there? What happens if there is subsequent swelling? Is it a good idea to put something sticky on fragile skin? I, personally, do not recommend the use of steristrips.

If you can moisturize the surrounding skin without disturbing the wound and flap, do so. Also, there are a number of products that you can use to leave a thin film barrier on the skin. This can be used on the periwound skin to help protect it from exudate. Also, if you do need to use something sticky then these barrier films can help reduce skin stripping(23). But be aware that it does increase how well the adhesive will stick to the skin.

Secure the flap in place with a simple dressing that will maintain a warm, moist wound environment and not cause any further trauma upon removal. Foams and hydrofibres are a good choice, as they will absorb quite a lot of exudate if the wound is weeping. They keep the area warm and provide a certain amount of cushioning from further damage. Hydrocolloids can be used if there is very low exudate, they will also protect the wound from frictional damage(24). If there are any signs of infection, or if the wound was highly contaminated, hydrocolloids are not recommended. There is also an acrylic dressing that is completely see through. This dressing has an acrylic absorbent pad and a film backing, it has the same benefits and drawbacks of the hydrocolloid with the added benefit of being able to see through it(25). Consider using an antimicrobial if the wound is highly contaminated, covers a large area, or if the patient is immunocompromised.

Put the date on the dressing and draw an arrow showing the direction of the flap (which is also the direction for removal).

As mentioned earlier, the healing process in the older person still happens as it does in the younger person, it might just take a bit longer. If we do frequent dressing changes we risk disturbing the new tissue because the tensile strength of wounds in older people is less, therefore it takes less force to interrupt wound healing(1, 13). By putting on a dressing we can leave in place for at least 3 days we give the wound a good chance to start healing and for the flap to stabilize if it is going to survive.

If the area is suitable for compression then a good firm tubular bandage or two not only keeps the dressing in place but also helps to reduce oedema(26).

For wards/areas where there are a high number of skin tears it might be an idea to have skin tear packets which have everything you need and a quick overview of what to do. This kind of “just in time” education has been shown to improve nurse confidence and ability to apply wound dressings(27). But you would need to weigh up the potential benefits against the cost of making up the single-use kits.

Know what to do! Keep up to date with wound care principles; this can either be through face-to-face training, on-line training or just reading journal articles(28, 29). Trying to keep up with every dressing company’s products would consume all your waking hours, so don’t try! Get an idea of the generic categories of dressings and what that category does. Stick to the principles of wound bed preparation, then match your needs to the dressing category.

With all of our systemic risk factors as we age (such as co-morbidities, polypharmacy, poor nutrition and hydration, slower immune response, etc) our chances of healing in a timely fashion and with no complications are somewhat reduced. So in the case of skin tears and the older population, prevention really is better than cure. Some things that help prevent skin tears are:

Skin tears, especially those on the lower leg, carry with them the risk of evolving into chronic ulcers. Hopefully, by following good wound bed preparation practices, moist wound healing principles and addressing the underlying risk factors which impair healing we can assist these wounds to follow a normal wound healing pathway. However, for some patients we will not be able to help them to heal. So it’s better to prevent the injuries we can.

1. Toy, L.W., How much do we understand about the effects of ageing on healing? Journal Of Wound Care, 2005. 14(10): p. 472.

2. Hermans, M.H.E. and T. Treadwell, An Introduction to Wounds, in Microbiology of Wounds, S. Percival and K. Cutting, Editors. 2010, CRC Press: Boca Raton, Fla. p. 83-134.

3. Hall, G. and T.J. Phillips, Estrogen and skin: the effects of estrogen, menopause, and hormone replacement therapy on the skin. Journal Of The American Academy Of Dermatology, 2005. 53(4): p. 555-568.

4. Kanda, N. and S. Watanabe, Regulatory roles of sex hormones in cutaneous biology and immunology. Journal Of Dermatological Science, 2005. 38(1): p. 1-7.

5. Callaghan, T.M. and K.P. Wilhelm, A review of ageing and an examination of clinical methods in the assessment of ageing skin. Part I: Cellular and molecular perspectives of skin ageing. International Journal Of Cosmetic Science, 2008. 30(5): p. 313-322.

6. Velarde, M.C., et al., Mitochondrial oxidative stress caused by Sod2 deficiency promotes cellular senescence and aging phenotypes in the skin. Aging, 2012. 4(1): p. 3-12.

7. Zouboulis, C.C. and E. Makrantonaki, Clinical aspects and molecular diagnostics of skin aging. Clinics In Dermatology, 2011. 29(1): p. 3-14.

8. Levakov, A., et al., Age-related skin changes. Medicinski Pregled, 2012. 65(5-6): p. 191-195.

9. Farage, M.A., et al., Clinical implications of aging skin: cutaneous disorders in the elderly. American Journal Of Clinical Dermatology, 2009. 10(2): p. 73-86.

10. Carville, K., Wound Care Manual. 5th ed2007, Osborn Park, WA: Silver Chain Nursing Association.

11. Cereda, E., et al., Fluid intake and nutritional risk in non-critically ill patients at hospital referral. The British Journal of Nutrition, 2010. 104(6): p. 878-885.

12. Nazarko, L., Part one: consequences of ageing and illness on skin. Nursing & Residential Care, 2005. 7(6): p. 255-257.

13. Thomas, D.R. and N.M. Burkemper, Aging skin and wound healing. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 2013. 29(2): p. xi-xx.

14. Moore, K., Cell Biology of Normal and Impaired Healing, in Microbiology of Wounds, S. Percival and K. Cutting, Editors. 2010, CRC Press: Boca Raton, Fla. p. 151-186.

15. Karukonda, S.R., et al., The effects of drugs on wound healing--part II. Specific classes of drugs and their effect on healing wounds. International Journal Of Dermatology, 2000. 39(5): p. 321-333.

16. St John Ambulance Australia. Severe Bleeding. 2012 [cited 2014 6 July]; Available from: http://stjohn.org.au/assets/uploads/fact sheets/english/FS_bleeding.pdf

17. Yorkshire Palliative Medicine Clinical Guidelines Group, Guidelines on the management of bleeding for palliative care patients with cancer - summary, 2009.

18. Harding, K., et al., Evolution or Revolution? Adapting to complexity in wound management. International Wound Journal, 2007. 4 Suppl. 2(2): p. 1-12.

19. Fletcher, J., Wound assessment and the TIME framework. British Journal of Nursing, 2007. 16(8): p. 462-4.

20. Wilkins, R.G. and M. Unverdorben, Wound cleaning and wound healing: a concise review. Advances in Skin & Wound Care, 2013. 26(4): p. 160-163.

21. Atiyeh, B.S., S.A. Dibo, and S.N. Hayek, Wound cleansing, topical antiseptics and wound healing. International Wound Journal, 2009. 6(6): p. 420-430.

22. Fernandez, R., R. Griffiths, and C. Ussia, Effectiveness of Solutions, Techniques and Pressure in Wound Cleansing. JBI Best Practice Technical Report, 2006. 2(2).

23. 3M Australia. 3M™ Cavilon™ No Sting Barrier Film. 2006 [cited 2014 5 July]; Available from: http://solutions.3m.com.au/wps/portal/3M/en_AU/AU_Cavilon/Home/HC_Professionals/Skin_Wound/.

24. ConvaTec. DuoDerm Dressing Range. 2011 October 2, 2011]; Available from: http://www.convatec.com/en/cvtus-duodrrngus/cvt-portallev1/0/detail/0/1444/1847/duoderm-dressing-range.html.

25. 3M Gulf. 3M™ Tegaderm™ Absorbent Clear Acrylic Dressing. 2014 [cited 2014 6 July]; Available from: http://solutions.3mae.ae/wps/portal/3M/en_AE/Healthcare-Europe/EU-Home/Products/ProductCatalogue/?PC_Z7_RJH9U52300PI40IA1Q602S28E7000000_nid=BT1RVC6X99beHCSJM6GZJRgl.

26. Mölnlycke Health Care. Tubigrip. n.d. [cited 2014 6 July]; Available from: http://www.molnlycke.com/patient/en/Products/Wound-care-products/Tubigrip/ - About.

27. Kent, D.J., Effects of a just-in-time educational intervention placed on wound dressing packages: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Journal of Wound, Ostomy & Continence Nursing, 2010. 37(6): p. 609-614.

28. Robinson, B.K. and V. Dearmon, Evidence-based nursing education: effective use of instructional design and simulated learning environments to enhance knowledge transfer in undergraduate nursing students. Journal Of Professional Nursing: Official Journal Of The American Association Of Colleges Of Nursing, 2013. 29(4): p. 203-209.

29. Sherman, A., Continuing medical education methodology: current trends and applications in wound care. Journal Of Diabetes Science And Technology, 2010. 4(4): p. 853-856.

30. Watkins, P., Using emollients to restore and maintain skin integrity. Nursing Standard, 2008. 22(41): p. 51-57.

31. LeBlanc, K. and S. Baranoski, Skin tears: best practices for care and prevention. Nursing, 2014. 44(5): p. 36-46.

© 2015 Wound Care Resource All rights reserved | Web template modified from W3layouts